Stephen Hawking is the icon of individual achievement in the face of almost unimaginable adversity. A diagnosis of motor neurone disease is almost always a death sentence, and one more frightening than most. As the moving new film of Hawking’s life, The Theory of Everything, shows, he was a gifted 21-year-old student embarking on his Cambridge PhD in 1963 when his condition was discovered. Given two years to live, the young scientist went from cheerfully cycling around Cambridge to being told his body would waste away until he stopped breathing.

And yet Hawking lives: at 72, he is only a few years away from the average life expectancy for a British male. Not only has his body exceeded the expectations of medical science, but also his mind has flourished. Even as he has become nearly paralysed, the electronic voice synthesiser through which he speaks has become instantly recognisable: Hawking is the world’s most celebrated living scientist.

The achievements of those who succeed against terrible odds can sometimes intimidate the rest of us. I don’t suffer from any of those impediments, we think, and yet what do I have to show for it? But as the film demonstrates, all of us – however gifted – are products of collective action, the sum of the efforts and experiences (for good or for ill) of those around us.

Hawking’s work would surely have been impossible if it was not for his wife for quarter of a century, Jane. Love binds us to a partner regardless of the circumstances, but to commit to a relationship with a lover in the early stages of such a bleak prognosis – in the face of urgings not to – is the sign of a steely resolve.

Becoming engaged to Jane “changed my life”, Hawking would often reflect. “It gave me something to live for.” Being his de facto carer meant numerous sacrifices, not least when it came to her own career, and particularly as children arrived. Critics have suggested that the film is overly kind to Stephen Hawking and deviates from the memoirs of Jane, on which it is ostensibly based. Her own book suggests that he could be selfish, refused additional help, was condescending about her academic interests and ended their long marriage in a cruel way. But without her by his side, it seems Hawking would never have achieved his greatness.

He has also been sustained, of course, by the incredible collective effort of healthcare and medical science. As he himself has said in outspoken attacks on privatisation, without the NHS he would not have lived. His contributions to science – formidable as they certainly are – are themselves part of a vast collective endeavour.

Science is about building on and interacting with the work of others, an enterprise that stretches across the centuries. Hawking shared the 1988 Wolf prize for physics, for example, with his collaborator, Sir Roger Penrose. And then there’s his upbringing: we know that “cultural capital”, such as the vocabulary or education we inherit from our family, has a huge impact. All of which is to say that a great scientist is a team effort – as we all are.

The same goes for so many other heroes. One of my favourite examples is that of Rosa Parks, an undeniably courageous African-American woman who defied Alabama’s racial segregation laws on public transport in 1955. But she was not the first to do so, and neither was it something she did on an individual whim.

Parks was a prominent local activist in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; she worked with radical trade union activists; and the act of civil disobedience was one agreed with the NAACP and local trade union movement. It was the spur for a bus boycott – and was intended as such – and was a crucial moment in the birth of the US civil rights movement. It was possible precisely because her bravery was married to a much larger effort.

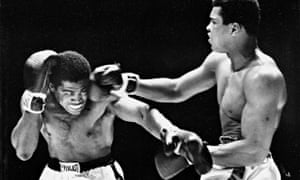

As in science and politics, so in sport. Think of Pelé, taught football by his parents and honed as a player in numberless games with his peers; Muhammad Ali, trained up by the likes of Chuck Bodak; or Michael Schumacher, whose parents worked extra jobs to support his racing dreams. Likewise, musicians and literary greats are schooled at often considerable expense, and inspired by the work of others. All of us – however talented or renowned – stand on the shoulders of others.

Despite all the evidence, the prevailing rugged individualism suggests those who flourish are the authors of their own success. But the rights and freedoms we enjoy today were won by a colossal, multi-generational struggle on the part our ancestors, who also bequeathed their collective knowledge and experiences. We depend on a hugely expensive system of education, not just for ourselves, but also to train those we, in turn, depend on; a health service to keep us – and our neighbours – from suffering the worst effects of catastrophic illnesses; infrastructure that keeps society functioning. As social animals, we depend on the interaction, interest and love of those around us. We are socially constructed beings, forming an immense dynamic system that cannot be understood by reducing it to its individual parts.

None of this is to erode the importance of the individual. The cliche that we are all unique is true; we all have individual agency, the ability to make choices, even if they are constrained by the environment in which we live. Though we are all contributing to a grand collective project, that project would not be possible without the unique contributions of millions of individuals. Understanding this would better allow each one of us to thrive: to overcome the collective, socially constructed injustices that serve as blocks on potential.

That is what I learn from a great man like Hawking. It is possible to be in awe of his talent and contributions, while understanding that none of it would have been possible without the involvement and efforts of countless others. The good or bad that we do has the fingerprints of others all over it. It is one reason we should all feel pride in the achievements of others. We will succeed together or we will fail together. We are all linked, arm by arm, whether we like it or not.

View all comments >